The latest Cowries and Rice podcast features Michigan State University History PhD candidate Hikabwa Decius Chipande discussing China’s stadium diplomacy in Zambia. Intriguingly, the enterprising hosts of the podcast, Winslow Robertson and Dr. Nkemjika Kalu, contacted Chipande in Lusaka after reading his “China’s Stadium Diplomacy: A Zambian Perspective” post on this blog.

In the interview (listen above), Chipande expands on his original contribution to explore several key aspects of the national and international politics of stadium construction in contemporary Zambia. Chipande shares his expert view on Zambian responses to the new arenas, inspired by Elliot Ross’s recent essay on the topic for Roads & Kingdoms, and contextualizes them within larger Chinese investments in mining and other sectors of the economy in south-central Africa.

Chipande is a recipient of the FIFA Havelange Research Scholarship for his doctoral dissertation on the social and political history of football in Zambia, 1950-1993. Reach out to him on Twitter at @HikabwaChipande.

Category: Hosting

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

“If you want to see the heart of China’s soft-power push into Africa,” writes Elliot Ross in a recent piece for Sports Illustrated’s “Roads & Kingdoms” series, “you’ll find it in the continent’s new soccer stadia.”

I am one of the many Zambians saddened that most of our national team matches are now staged at the Chinese-built Levy Mwanawasa Stadium in Ndola, an industrial town on the Copperbelt 200 miles north of the capital, Lusaka. This is not only because I live in Lusaka, where the team used to play its home games, but also because the move greatly diminishes, if not erases, the deeper significance of historic football venues.

It was in Lusaka’s then-newly constructed Independence Stadium on October 23, 1964, that the Union Jack was lowered and the new Zambian flag raised at midnight in a sumptuous ceremony attended by the Princess Royal and Kenneth Kaunda’s new cabinet. The following day, the stadium hosted the final of the Ufulu (independence) tournament. Ghana’s Black Stars, reigning African champions, beat Zambia 3-2 in front of about 18.000 spectators. From then on, almost all important international matches (as well as domestic cup finals) were played at Independence Stadium, a local example of how stadiums in postcolonial Africa, “quickly became almost sacred ground for the creation and performance of national identities” (Alegi, African Soccerscapes, p. 55).

Occasionally, Dag Hammarskjöld Stadium in Ndola hosted big matches. Constructed by the Ndola Playing Fields Association during the colonial era, this ground was rechristened in honor of the Swedish Secretary-General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld, who died in 1961 in a plane crash near Ndola. After the British colony of Northern Rhodesia became independent Zambia, the stadium was donated to the Ndola City Council. As the largest stadium in the Copperbelt, the traditional hub of football in the country, it hosted virtually every important match in the region.

In January 1986, the Zambian government bought into the idea of hosting the 1988 African Nations Cup finals. Mary Fulano, then a member of the Central Committee in charge of sport, informed the public that the government had started renovating both Independence and Dag Hammarskjöld stadiums. But in December 1986, after Dag Hammarskjöld stadium had been demolished for its planned reconstruction, Youth and Sport minister Frederick Hapunda announced that government had withdrawn its bid to host the 1988 tournament.

Copperbelt residents complained that they needed their beloved stadium, but the government kept on issuing empty promises. Surprisingly, two decades later, when an opportunity arose to build a new stadium in Ndola courtesy of China, the Zambian government opted for a completely new Levy Mwanawasa Stadium in a different area, thereby burying the rich history of Dag Hammarskjöld Stadium.

In 2012, I attended the inauguration of the Levy Mwanawasa Stadium: a 2014 World Cup qualifier between Zambia and Ghana (see my blog post about it here). The atmosphere at the venue was similar to the one described by Elliot Ross at the Estádio Nacional do Zimpeto in Maputo. Unlike the game in Maputo, however, there was no pushing and shoving at Levy Mwanawasa, thanks to plenty of available space and sound event management. But the stadium was so vast that the crowd could not sing and chant cohesively, or create the electrifying atmosphere so many of us treasure at football grounds.

The ignominuous end for Independence Stadium in Lusaka came after FIFA inspectors in 2007 declared it unsafe for international matches. As a temporary solution, the Football Association of Zambia moved internationals to Nkonkola Stadium in a small mining town on the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo. Bolstered by another Chinese loan, the Zambian government then erected a new National Heroes Stadium directly across from Independence Stadium and the graves of national team members who perished in the Gabon air crash of 1993.

The demolition of Independence Stadium prompted many people to wonder why the government chose not to renovate the hallowed ground and build the Chinese-funded stadium somewhere else in Lusaka. While younger Zambians tend to like the new sporting arenas, many older fans lament the disappearance of stadiums they associate with the stories of their personal lives, their memory, their past.

Regardless of age and status, Zambians are very much aware of “Chinese soft diplomacy.” People know that Chinese stadiums have less to do with friendship or mutual cooperation and more with gaining access to Africa’s material resources. Yet there is very little that can be done about it because the government does not consult with citizens on economic deals with China. There is criticism about Chinese firms bringing very cheap laborers to work in construction sites. But there seems to be a general feeling among the population that it is acceptable for the Chinese to build stadiums and other infrastructure in exchange for copper because the alternative is allowing Zambia’s political leaders to pocket the profits from this wealth.

—

*Hikabwa Chipande is a PhD candidate in History at Michigan State University. He is a recipient of the FIFA Havelange Research Scholarship for his doctoral dissertation on the social and political history of football in Zambia, 1950-1993. Follow him on Twitter at @HikabwaChipande

Guest Post by Liz Timbs (@tizlimbs)

Guest Post by Liz Timbs (@tizlimbs)

“We indeed have a crisis of monumental proportions. We don’t have a crisis of talent, we have a crisis of putting everything together,” thundered South African Sport and Recreation Minister Fikile Mbalula following South Africa’s 3-1 loss to Nigeria in Cape Town on Sunday, which eliminated the hosts from the 2014 African Nations Championship.

Mbalula publicly lambasted the national team, declaring that what he witnessed “was not a problem of coaching, it was a bunch of losers.” This “bunch of losers” and “unbearable useless individuals,” Mbalula continued, humiliated their country: “In Africa we have won nothing—we are the laughing stock. Even Madiba Magic would not have worked. This generation of players we must forget.”

Danny Jordaan, president of the South African Football Association and ex-CEO of the 2010 World Cup Local Organizing Committee, also criticized Bafana’s performance in the media, though in slightly less forceful terms than Mbalula. Jordaan saw the team’s elimination as an embarrassment, noting that SAFA had been “dismissive and even insulting to the quality of football on the continent.” He highlighted a deficiency in the “preparations, philosophy and technical staff.”

The reaction from Bafana Bafana head coach, Gordon Igesund, was decidedly tamer. “There are no excuses,” Igesund declared, “We lost to a better side . . . at the end of the day we have to look at ourselves and admit we were just not good enough even though we gave it our best shot.” Midfielder Siphiwe Tshabalala echoed Igesund’s understated honesty in his comments to the press. He apologized for the team’s debacle, adding that: “we are hurting and we know the nation is also hurting and we are not proud of not doing well but we just have to apply ourselves better in the future.”

Tshabalala and Igesund’s comments cut straight to the realities of why South Africa lost to Nigeria. Bafana certainly did not lose because goalkeeper Itumeleng Khune withdrew due to an ankle injury that threatened his participation in an upcoming Kaizer Chiefs league match against Mamelodi Sundowns. Let’s acknowledge the painful reality and move on: The South African national team is, at best, mediocre; we have to face this truth.

What makes digesting this bitter pill more difficult is that Nigeria did not even field her best team. The CHAN competition is limited to home-based players, which meant that Nigerians playing in European clubs were ineligible for selection unlike most Bafana regulars who ply their trade in the well-endowed domestic Premier Soccer League. Despite this apparent advantage, Bafana was no match for a team of young Nigerian players with limited experience in international competition. The visitors delivered three staggering blows and came close to a fourth before Bernard Parker scored a consolation penalty for the hosts.

Jordaan and Mbalula’s frustration with the national team is understandable. South African fans were frustrated watching the game. The problem is not that politicians and football officials were voicing their legitimate concerns, but rather the way in which they were framing these issues. These micro-level critiques, while useful in expressing frustration and releasing tension, are unproductive for getting to the root of South African football’s larger problems.

While not solely responsible, SAFA should be assisting in whatever way possible to develop talent at the grassroots level in order to eventually effect positive change at the highest level. Jordaan stated that SAFA is aware of the need for “big changes” at “grassroots level,” adding that “If we want to build a winning team for the future we have to have efficient structures in place right from school level.” Yet this vision is narrowly framed in terms of how this vaguely defined development would result in better showings by the senior national team.

Jordaan is right that grassroots development is desperately needed. But perhaps not in the ways he and others like Mbalula are suggesting. Mohlomi Maubane spoke to this important issue in a 2012 post on this blog. “SAFA’s understanding of the ‘bigger picture’ in domestic football is confined to four-year cycles for the men’s national team,” Mohlomi wrote. “But local football needs sound management, serious youth development for boys and girls, better coaches’ training, and infrastructural improvements at the grassroots.”

Using football as a tool for development not only helps to nurture athletic talent (as Jordaan noted) but also works to build healthy, productive members of society. As the remarkable work of Izichwe Football Club in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal demonstrates, this kind of development takes time, work, and resources. While the results won’t be seen right away, South African football can move forward through community-based, player-centered, long-term, sustainable approaches to youth and coaching development.

Minister Mbalula was correct in one regard: “We indeed have a crisis of monumental proportions.” Hopefully, the latest Bafana loss will inspire South African sport administrators and partners to invest the necessary resources and knowledge to go beyond crisis management and move closer to fulfilling South Africa’s great football potential.

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs.

The Football Scholars Forum, an international online think tank, convened on November 14 to discuss Football in the Middle East. The conversation focused on a special issue of the academic journal Soccer and Society, edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi. The group began by noting that while football has been a critical force in broader political and cultural developments in the region, there is little institutional support for studying the game in the Middle East.

The Football Scholars Forum, an international online think tank, convened on November 14 to discuss Football in the Middle East. The conversation focused on a special issue of the academic journal Soccer and Society, edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi. The group began by noting that while football has been a critical force in broader political and cultural developments in the region, there is little institutional support for studying the game in the Middle East.

The ensuing 90-minute discussion demonstrated the value of scholarly collaboration and research on the game. The group explored a dizzying number of topics and territories, including football as a source of unity and hope and as a site of political and ideological conflict; the 2022 World Cup in Qatar; soccerpolitics in Turkey; sport and Islamism; Palestinian and Iraqi Kurdish women’s teams; and football films and poetry.

For a Storify Twitter timeline click here.

Download the mp3 of the session here.

Guest Post by Khaya Sibeko (@KhayaSibeko1)

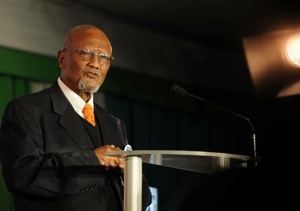

JOHANNESBURG—On October 30, 2013, Leepile Taunyane, South Africa’s legendary football administrator, died at the age of 85. It would not be an exaggeration to compare his passing to the burning of a national archive.

Born in Alexandra, Johannesburg, Taunyane grew up playing football in the streets and then joined Rangers in the early 1950s, a club known for its technical prowess and feared for its lineup stacked with ex-convicts. After hanging up his boots, in the 1960s Taunyane started a career as a football organizer and served as principal first at Alexandra High School and then at Katlehong High.

His administrative career saw him involved in every major transformation in the South African game. Taunyane worked with Bethuel Morolo at the South African Bantu Football Association and then with his successor, George Thabe. In the mid-1980s, an era of massive political and social upheaval in apartheid South Africa, Taunyane led the Transvaal affiliate of Thabe’s Africans-only organization to throw its weight behind the National Soccer League. A precursor of today’s Premier Soccer League, the NSL was a new, racially integrated league launched in 1985 as a break away league from Thabe’s NPSL. Taunyane became the NSL’s first president.

In a recent City Press article, Premier Soccer League and Orlando Pirates chairperson, Irvin Khoza honored his mentor: “I was his student when he was a teacher. He recruited me at the tender age of 14 to become a member of the Alexandra Football Association. We later rubbed shoulders in the national league and federation structures. Dr. Taunyane personifies the values that govern my decision-making and actions, consciously and unconsciously.”

Taunyane was “the last of the Mohicans” of football administrators of a venerable generation. Even when others around him found the temptations of post-isolation football too much to resist, Taunyane remained a diligent and incorruptible servant of the beautiful game. It was no surprise when, a few years ago, the PSL bestowed the honorific title of Life President.

It is not enough to celebrate and award titles, of course. By publicly recognizing Taunyane’s great legacy, local football administrators should strive to follow his exemplary managerial conduct. That would be the best way to remember and honor a “son of the soil” who spared neither time nor energy in the service of football and education.

Undoubtedly, the gods of South African football have placed Taunyane alongside Bethuel Mokgosinyane, Solomon Senaoane, Dan Twala, Albert Luthuli, Henry Ngwenya, George Singh and so many elders of the distant past, men whose efforts shaped our football in the era of segregation and apartheid. Without the contributions of men like Taunyane, South Africa would never have hosted the 2010 World Cup and the PSL would not be among the ten richest leagues in the world.

Guest Post by *Liz Timbs

In Zulu culture, an imbiza is a large ceramic pot used for brewing utshwala (sorghum beer). This vessel enables the fermentation of a fluid that facilitates communication with the amadlozi (ancestors) and lubricates social interactions. Taking my cue from this vernacular technology, I am launching Imbiza: A Digital Repository of 2010 World Cup Stadiums and Fan Parks—an open access collection of primary sources for brewing ideas and encouraging public dialogue about this defining event in South Africa after apartheid.

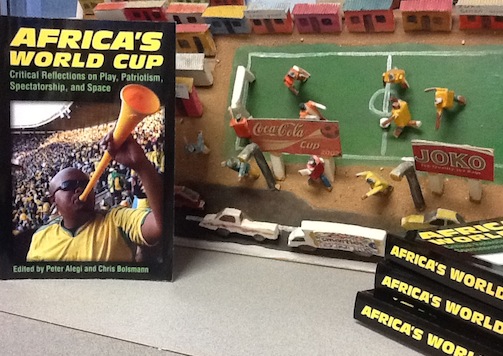

The potential for this digital project crystallized during a recent session of the Football Scholars Forum on Alegi and Bolsmann’s new book Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space. During the online discussion, the conversation turned to ways of integrating academically-oriented essays like those in Africa’s World Cup with web-based images, videos, and texts produced by non-specialists for a general audience.

While this idea was initially framed in terms of what could be done for next year’s World Cup in Brazil, the historian in me started thinking about how a project like this could help further understand the 2010 World Cup. Serendipitously, I was also searching for a suitably interesting project to fulfill the requirements of my Cultural Heritage Informatics Fellowship, a program run by Dr. Ethan Watrall at Michigan State University in collaboration with MATRIX, the digital humanities and social sciences center. After some more pondering and a chat with Peter Alegi, my PhD supervisor (and curator of this blog), I decided to go for it.

In building the Imbiza repository, I aim to integrate openly accessible texts, images, sounds, and videos that capture fans’ perspectives and experiences at World Cup stadiums and fan parks. I’ve already begun to collect materials, so accumulating enough sources surely will not be an issue. Among the main challenges for the project will be organizing, tagging, and presenting the items in an accessible, informed, and compelling manner. My hope is that this project will build a model that can be replicated in the study of future World Cups and mega-events, allowing for critical engagement as well as nostalgic reflection.

I do not want this to be a solitary academic venture; that would get away from the whole point of it. I want Imbiza to stand as a testament to the potential of digital technologies for collaborative knowledge production. I am limited by geography, time, and finances in building this archive from my base in East Lansing, but digital platforms, like this one, can get around some of these obstacles.

So consider this blog post a call; a call for submissions, ideas, and inspiration to make Imbiza a success. With the 2014 World Cup in Brazil just a few months away, the time is now to reflect on the legacies of the 2010 World Cup. Ke nako!

—

Follow this project’s progress on Twitter via the hashtag #Imbiza and on the project blog. If you have comments, submissions, sources, or questions, please contact me at imbizaarchive AT gmail.com.

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs.

The Football Scholars Forum, an online fútbol think tank I co-founded at Michigan State University, recently launched its 2013-14 season. On October 24, FSF held a lively discussion of Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space, a newly published collection I edited with Dr. Chris Bolsmann, a South African sociologist based in the UK.

The 90-minute event opened with a consideration of the book’s attempt at blending scholarly and journalistic approaches to exploring the game and its broader implications. The editors and several chapter authors in attendance talked about the process of writing and editing, as well as their experience working with an academic press on a topic with potentially broad appeal.

The book, much of it written in the first person as a loving critique of the 2010 tournament, demonstrates how the FIFA World Cup story is entangled in a web of national and international politics, sporting culture, and global capitalism. Many interventions linked South Africa 2010 to Brazil 2014, particularly through the public financing of expensive and unsustainable new World Cup stadiums in countries with dysfunctional schools and hospitals and high rates of poverty and inequality. The online conversation also featured Luis Suarez’s handball against Ghana and the contradictory legacies of this “African” World Cup.

Participants logged in from half a dozen countries in North America, South America, Africa, and Europe. In attendance: Andrew Guest, Chris Bolsmann

, Christoph Wagner

, David Patrick Lane,

David Roberts,

Derek Catsam,

Jacqueline Mubanga,

Raj Raman,

Orli Bass

, Rwany Sibaja,

Laurent Dubois

, Achille Mbembe

, Jordan Pearson, Sean Jacobs, and Alex Galarza (all via Skype); and Liz Timbs,

Dave Glovsky,

Alejandro Gonzalez, and

Peter Alegi (in East Lansing).

For a Storify Twitter timeline of the event click here.

The audio recording of the discussion is freely available here.

The next Football Scholars Forum event on November 14 will focus on Soccer in the Middle East, a special issue of the journal Soccer and Society (2012), edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi.