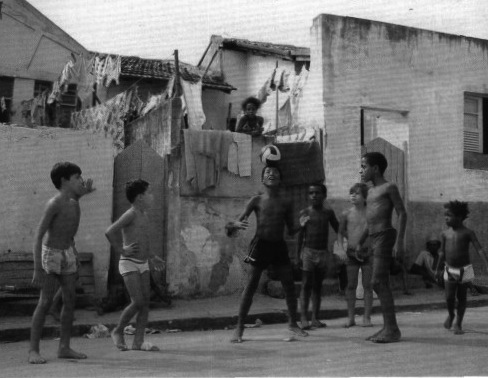

Image: Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C.

Image: Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C.

Cross-posted from The Allrounder

[First published on November 13, 2014]

We don’t just watch sports – we speak and hear sports. To find out how language shapes our lives as fans, we asked some of our writers to tell us about the ways that people talk sports in English and their native languages. Kay Schiller hails from Munich, fellow historian Peter Alegi grew up in Rome, media scholar Markus Stauff lives in the Netherlands, and sociologist Pablo Alabarces teaches at the University of Buenos Aires. Together, they offer a Rosetta Stone of sports talk.

You’ve all lived for a time in English-speaking countries. Did anything in particular strike you – say, the first times you went to a stadium or watched a match on television – about the ways that native speakers of English talk about their sports?

Kay Schiller: I have lived in the UK since 1997. One of the things that struck me as a non-native speaker when going to see Chelsea, Spurs, Liverpool, ManU, or, more recently, Blackburn Rovers was that I had a tremendously hard time understanding the terrace chants, despite being quite fluent in English. I suppose that this is similar to what English fans experience when they attend a Bundesliga match.

Thankfully, there are now websites that explain what you hear in the stadium. You can learn that Blackburn Rovers fans at Ewood Park have several profane chants for Burnley, such as “Burnley are s**t s**t s**t , they always gonna be s**t.” One major difference with Germany is that while this kind of folklore can be found in the supporters’ curves of stadia, you wouldn’t hear otherwise respectable-looking people participating in chants like these – or middle-aged ladies calling the referee a c***.

I’m not sure what this suggests about the different football cultures of England and Germany, or culture more generally, but I find it worthy of note. Perhaps it’s reassuring that even with all-seater stadia and the continuous jacking-up of gate prices in English football, some things do not change.

Peter Alegi: At venerable Fenway Park in Boston, sitting in the bleachers with my dad (obstinately wearing a Yankees cap), the usual chant we heard was: “Yankees suck!” At New Haven Coliseum, where my older brother and I followed minor league ice hockey, it was: “Shoot the puck!” At basketball and American football games, giant electronic scoreboards demanded chants of “Deeeeee-fe-nse!”

This was a world away from the Italian football stadiums and basketball arenas I grew up with.

What first struck me in the U.S. was a lack of spontaneity in the language of fans at the grounds. The PA announcer, the scoreboard, and recorded music directed the orality of the crowd. Maybe this was because of the corporate nature of American sports, with its top-down manufactured stadium experience that transforms fans into consumers. It’s also hard to chant and sing when spending so much time, money, and energy eating and drinking during games. In any case, the second thing that hit me about the U.S. context was the lack of creativity in the language. Much of the spoken word among fans, chants and commentary alike, seemed very direct and not terribly imaginative, a bit like the English language!

In Italy, our oral culture at the stadium was far more creative. I remember sitting in the stands listening to self-appointed bards who would rise to recite absorbing monologues in the vernacular (dialects are hugely important and richly diverse in Italy). These men (rarely were they women) explained the causes of our striker’s inexplicable impotence or the reasons for the referee’s situational ethics. The language was often metaphorical, indirect. The best insults were the ones delivered with a perfect balance of grit, humor, and linguistic dexterity. Even my intellectual Roman mother, with a PhD in Italian literature, relished such vulgar poetic performances (“vulgus” in Latin means ordinary people, after all). This creative genius came through in the songs we sang. Fans developed an art of crafting lyrics and combining them with a dizzying range of musical sources: classical (Beethoven’s “Ode To Joy” was a favorite); operatic (Verdi, of course); patriotic compositions (“La Marseillaise”); marches (John Philip Sousa!); folk/traditional (“La Società dei Magnaccioni,” “O Sole Mio,” and “Auld Lang Syne”); partisan resistance (“Bella Ciao”), and loads of pop (from “Yellow Submarine” to Antonello Venditti’s “Roma, Roma, Roma”).

Eventually, I came to appreciate the comfort and safety of U.S. stadiums and arenas. But to this day, their canned and often lifeless aural culture makes me nostalgic of home.

Click here to read on.