This year’s Africa Cup of Nations is underway in Equatorial Guinea. RFI talks about African football and media coverage with Peter Alegi, an authority on the game in Africa and Professor of History at Michigan State University in the United States. [full text here.]

Click below to listen to the interview. (iOS users click here.)

Tag: Africa Cup of Nations

The 2015 African Nations Cup begins on January 17 in Equatorial Guinea. The oil-rich dictatorship, a former Spanish colony with a population of 736,000, agreed to host the tournament on short notice after Morocco pulled out due to fears related to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

Africa’s most important tournament is organized by the Confederation of African Football (CAF), a trailblazing pan-Africanist institution born at the dawn of the era of decolonization. Joining the world body, as I’ve written elsewhere, was an honorable, quick, and inexpensive way for newly independent nations to assert their full membership in the international community.

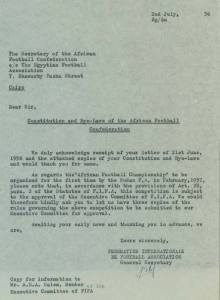

CAF took tangible shape at the 1956 FIFA Congress in Lisbon. There, delegates from Egypt, Sudan, and South Africa convened to draft a constitution and by-laws. The men also decided to organize a continental championship. Ethiopia was also involved in the discussions, but Yidnecatchew Tessema was unable to travel to Lisbon. The African proposal was later sent to FIFA for review and approval (see image at left).

On February 8, 1957, football officials from Sudan, Egypt, Ethiopia, and South Africa convened at Khartoum’s Grand Hotel to formally launch CAF. Fred Fell, a white man representing apartheid South Africa, was invited because his country was a member of FIFA and the Africans did not wish to be perceived as undiplomatic. In the meantime, the white South African football association gingerly debated the composition of the national team. However, the authorities Pretoria opposed a mixed selection and the white football establishment did not challenge the policy.

There are conflicting accounts about what happened next. CAF officials stated that they promptly excluded South Africa in a show of unequivocal pan-African solidarity. Fell and white South African football put forward a different story: they claimed they withdrew the team prior to any sanctions due to the team’s impending tour to Europe as well as security concerns linked to the ongoing Suez Crisis. Unfortunately, the minutes of the meeting at CAF were later destroyed in a fire so we may never know the exact truth of the matter. What is certain is that the South African issue did not disappear. To the contrary, the struggle against apartheid in football would become a powerful bond that united CAF and nearly all African nations for three decades.

South Africa’s absence in 1957 meant that only three teams, comprised of amateurs, participated in the inaugural African Nations Cup. Ethiopia, which had been drawn to play against South Africa, received a bye into the final. Egypt defeated hosts Sudan 2–1 and then dispatched Ethiopia 4–0 in the final watched by a crowd of 30,000 at the Stade Municipal. All four goals were scored by striker Mohammed Diab El-Attar “Ad Diba.” “Those were unforgettable matches,” Ad Diba recalled in an interview in 2001. “The success of this championship and its popularity amongst the Sudanese encouraged the African federation to organize a tournament on a biennial basis and to be played in a different country each time,” he said. Ad Diba made history again eleven years later in Addis Ababa, when he refereed the Afcon final between Congo (DRC) and Ghana (see video).

In those early days, CAF brought to life Kwame Nkrumah’s dream of a United States of Africa. At the same time, football provided a rare form of national culture, unity, and pride in postcolonial Africa.

Today, the African Nations Cup has transformed itself into a globalized commercial event with multinational corporate sponsors, matches on satellite television and online, many European coaches, and most players on the sixteen squads employed by European clubs. It is a far cry from 1957. And yet an alluring contradiction has endured: the Afcon showcases Pan-African solidarity while triggering 90-minute nationalism.

The Confederation of African Football has announced that Equatorial Guinea will replace Morocco as host nation for the 2015 African Nations Cup, the continent’s oldest and most prestigious international tournament.

The decision followed “fraternal and fruitful discussions” between CAF and Equatorial Guinea’s President Obiang, according to CAF’s official statement. Matches will be played in Malabo, Bata, Mongomo and Ebebiyin. The draw is scheduled for December 3 in Malabo.

The oil-rich former Spanish colony, population 736,000, previously co-hosted the tournament, with Gabon, in 2012.

CAF’s announcement brought a controversial and increasingly tense saga to a close. Morocco’s decision to back out of its commitment to stage the Nations Cup came in the wake of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The North African nation’s withdrawal drew passionate criticism from many fans and observers in Africa and overseas.

Writing for The Guardian’s Comment is Free, Sean Jacobs (the South African founder of the Africa Is A Country website) argues that “a mix of politics, opportunism and self-interest seem to be behind Morocco’s decision.”

The incident, Jacobs explains, is evidence of Morocco’s “difficult relationship with nations south of the Sahara. African migrants, some on their way to Europe, regularly complain about harassment, violence and xenophobia.”

James Dorsey’s The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer blog took a similar tack. “Morocco can’t escape the impression that its decision was informed by prejudice,” especially within the context of a long and complex history of economic, cultural, and political relations between North African countries and sub-Saharan African nations. And, of course, fear shaped the decision as well. Fear, specifically, “about the possible impact of an Ebola case on tourism that accounts for an estimated ten percent of Morocco’s gross domestic product.”

Morocco’s seemingly contradictory decision not to host the Nations Cup in January but to go ahead and stage the FIFA World Club Cup next month sparked more criticism.

In the end, Africa’s grandest football show will go on thanks to Issa Hayatou, CAF’s president for the past 26 years, and President Obiang, Africa’s longest serving autocrat–in power since 1979 and at the head of the ruling Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea that holds 153 of 155 parliamentary seats.

This last-minute African Nations Cup resolution reminds me of FIFA General Secretary Jerome Valcke’s statement during the massive 2013 Confederations Cup protests in Brazil: “less democracy is sometimes better for organizing a World Cup.” And, in this case, it seems to work for an African Nations Cup too.