The Football Scholars Forum, an international online think tank, convened on November 14 to discuss Football in the Middle East. The conversation focused on a special issue of the academic journal Soccer and Society, edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi. The group began by noting that while football has been a critical force in broader political and cultural developments in the region, there is little institutional support for studying the game in the Middle East.

The Football Scholars Forum, an international online think tank, convened on November 14 to discuss Football in the Middle East. The conversation focused on a special issue of the academic journal Soccer and Society, edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi. The group began by noting that while football has been a critical force in broader political and cultural developments in the region, there is little institutional support for studying the game in the Middle East.

The ensuing 90-minute discussion demonstrated the value of scholarly collaboration and research on the game. The group explored a dizzying number of topics and territories, including football as a source of unity and hope and as a site of political and ideological conflict; the 2022 World Cup in Qatar; soccerpolitics in Turkey; sport and Islamism; Palestinian and Iraqi Kurdish women’s teams; and football films and poetry.

For a Storify Twitter timeline click here.

Download the mp3 of the session here.

Month: November 2013

Football and Independence in Zambia

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

LUSAKA—On a rainy Friday evening at the Pamodzi Hotel, Zambia Open University Professor Ackson Kanduza, president of the Southern African Historical Society, convened a forum based on my paper “Football and Independence in Zambia: A Political and Social History 1950s-1964.”

Part of my doctoral research on colonial and postcolonial Zambian football, the paper draws on archival, newspaper, and oral sources to argue that the changing culture of the African game influenced the anti-colonial nationalist struggle by fighting racial segregation and promoting African leaders to highly visible and prestigious administrative positions before independence.

In the early 1960s, colonial racism in then-Northern Rhodesia was still intense. Segregation kept Africans out of European-owned shops and forced black customers to shop through a window instead; Africans were not allowed to enter whites-only train carriages and buses; and jobs paying higher wages were reserved for whites.

But in 1961-62, black and liberal white businessmen founded the nonracial (racially mixed) National Football League. A black man, Tom Mtine, was named chairman of an otherwise white-dominated league executive. Two years prior to independence, the NFL permitted black players to be on the same teams as whites, and Africans were also allowed to represent the territory in international competitions. The emergence of black administrators like Tom Mtine and the game’s function as a “neutral” cultural form among people speaking 73 languages helped to assert black power as well as a sense of Zambian-ness that cannot be ignored in the history of Zambia.

An audience of both academics and members of the general public posed interesting questions and offered constructive comments. Most participants agreed with me that these sporting events signified an important step towards political freedom. Some noted that as Zambians celebrated their country’s 40th independence anniversary, my historical evidence about black leaders in football and the hosting of an international football tournament in 1964 to celebrate the nation’s birth would be highly appreciated by millions of Zambians. The discussion also grappled with the seemingly contradictory evidence that the British believed the game to be part of the “white man’s burden” while local people used it to fight colonial oppression.

“I did not know that our football has such a rich history,” said Pride Mwaanga; “I was wondering about the connection between football and independence, but now it makes sense!” Other participants asked why this rich history of Zambian football has not yet been explored. Echoing the conclusions of Marissa Moorman’s recent history of music and nationhood in the musseques (shantytowns) of colonial Luanda, Angola, audience members highlighted how, unlike anti-colonial political leaders, Zambian football administrators and players’ contributions to building the Zambian nation are not recognized in typical historical accounts.

Participants also stressed the need to publish biographies of past footballing greats such as “Ucar” Godfrey Chitalu, Dickson Makwaza, John “Ginger” Pensulo and many, many others. Professor Moses Musonda, Zambia Open University Deputy Vice Chancellor, pointed out that we need more scholars to research and write the history of football in Zambia, otherwise we are going to lose this valuable past.

Other interesting contributions came from Mrs. Kanduza and, again, from Prof. Musonda, who both gave testimonies of how they experienced leisure activities in welfare centers during the colonial era. These social centers played a critical role in the development of football. Prof. Musonda stated that Europeans enforced separate social institutions such as welfare halls to make sure that young Africans did not have the opportunity to challenge young Europeans in sport. Ironically, the same welfare centers and sporting facilities helped African men and women build their self-esteem and were later turned into avenues for political agitation.

Prof. Kanduza concluded the event by pointing out that a goal of the Zambia Open University is to organize forums that give opportunities to listen to unheard local voices. He highlighted how the research and discussion of “Football and Independence in Zambia” captures voices and conveys the historical experiences of African people through the prism of sport. The evening ended with a promise to organize more of these lively and insightful sessions in the near future.

—

*Hikabwa Chipande is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Michigan State University. He is currently in Lusaka researching the social, cultural and political history of football in colonial and postcolonial Zambia. Follow him on Twitter at @hikabwachipande

Guest Post by Khaya Sibeko (@KhayaSibeko1)

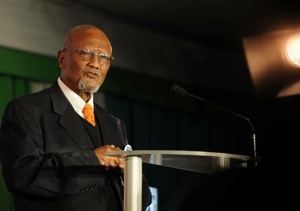

JOHANNESBURG—On October 30, 2013, Leepile Taunyane, South Africa’s legendary football administrator, died at the age of 85. It would not be an exaggeration to compare his passing to the burning of a national archive.

Born in Alexandra, Johannesburg, Taunyane grew up playing football in the streets and then joined Rangers in the early 1950s, a club known for its technical prowess and feared for its lineup stacked with ex-convicts. After hanging up his boots, in the 1960s Taunyane started a career as a football organizer and served as principal first at Alexandra High School and then at Katlehong High.

His administrative career saw him involved in every major transformation in the South African game. Taunyane worked with Bethuel Morolo at the South African Bantu Football Association and then with his successor, George Thabe. In the mid-1980s, an era of massive political and social upheaval in apartheid South Africa, Taunyane led the Transvaal affiliate of Thabe’s Africans-only organization to throw its weight behind the National Soccer League. A precursor of today’s Premier Soccer League, the NSL was a new, racially integrated league launched in 1985 as a break away league from Thabe’s NPSL. Taunyane became the NSL’s first president.

In a recent City Press article, Premier Soccer League and Orlando Pirates chairperson, Irvin Khoza honored his mentor: “I was his student when he was a teacher. He recruited me at the tender age of 14 to become a member of the Alexandra Football Association. We later rubbed shoulders in the national league and federation structures. Dr. Taunyane personifies the values that govern my decision-making and actions, consciously and unconsciously.”

Taunyane was “the last of the Mohicans” of football administrators of a venerable generation. Even when others around him found the temptations of post-isolation football too much to resist, Taunyane remained a diligent and incorruptible servant of the beautiful game. It was no surprise when, a few years ago, the PSL bestowed the honorific title of Life President.

It is not enough to celebrate and award titles, of course. By publicly recognizing Taunyane’s great legacy, local football administrators should strive to follow his exemplary managerial conduct. That would be the best way to remember and honor a “son of the soil” who spared neither time nor energy in the service of football and education.

Undoubtedly, the gods of South African football have placed Taunyane alongside Bethuel Mokgosinyane, Solomon Senaoane, Dan Twala, Albert Luthuli, Henry Ngwenya, George Singh and so many elders of the distant past, men whose efforts shaped our football in the era of segregation and apartheid. Without the contributions of men like Taunyane, South Africa would never have hosted the 2010 World Cup and the PSL would not be among the ten richest leagues in the world.

Guest Post by *Liz Timbs

In Zulu culture, an imbiza is a large ceramic pot used for brewing utshwala (sorghum beer). This vessel enables the fermentation of a fluid that facilitates communication with the amadlozi (ancestors) and lubricates social interactions. Taking my cue from this vernacular technology, I am launching Imbiza: A Digital Repository of 2010 World Cup Stadiums and Fan Parks—an open access collection of primary sources for brewing ideas and encouraging public dialogue about this defining event in South Africa after apartheid.

The potential for this digital project crystallized during a recent session of the Football Scholars Forum on Alegi and Bolsmann’s new book Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space. During the online discussion, the conversation turned to ways of integrating academically-oriented essays like those in Africa’s World Cup with web-based images, videos, and texts produced by non-specialists for a general audience.

While this idea was initially framed in terms of what could be done for next year’s World Cup in Brazil, the historian in me started thinking about how a project like this could help further understand the 2010 World Cup. Serendipitously, I was also searching for a suitably interesting project to fulfill the requirements of my Cultural Heritage Informatics Fellowship, a program run by Dr. Ethan Watrall at Michigan State University in collaboration with MATRIX, the digital humanities and social sciences center. After some more pondering and a chat with Peter Alegi, my PhD supervisor (and curator of this blog), I decided to go for it.

In building the Imbiza repository, I aim to integrate openly accessible texts, images, sounds, and videos that capture fans’ perspectives and experiences at World Cup stadiums and fan parks. I’ve already begun to collect materials, so accumulating enough sources surely will not be an issue. Among the main challenges for the project will be organizing, tagging, and presenting the items in an accessible, informed, and compelling manner. My hope is that this project will build a model that can be replicated in the study of future World Cups and mega-events, allowing for critical engagement as well as nostalgic reflection.

I do not want this to be a solitary academic venture; that would get away from the whole point of it. I want Imbiza to stand as a testament to the potential of digital technologies for collaborative knowledge production. I am limited by geography, time, and finances in building this archive from my base in East Lansing, but digital platforms, like this one, can get around some of these obstacles.

So consider this blog post a call; a call for submissions, ideas, and inspiration to make Imbiza a success. With the 2014 World Cup in Brazil just a few months away, the time is now to reflect on the legacies of the 2010 World Cup. Ke nako!

—

Follow this project’s progress on Twitter via the hashtag #Imbiza and on the project blog. If you have comments, submissions, sources, or questions, please contact me at imbizaarchive AT gmail.com.

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs.

Punk Football for the Working Class

We play therefore we are.

That, in essence, is the sentiment that motivated a group of disaffected Red Devils’ fans opposed to Malcolm Glazer’s $1.5 billion takeover in 2003 of Manchester United to quit Old Trafford and form a new club: FC United of Manchester.

Punk Football, a terrific and profoundly humanistic new documentary film, chronicles FC United’s dramatic 2012-13 campaign which brought them to the brink of promotion to the North Conference League—five levels below the glitz and glamor of the English Premier League.

We are introduced to FC United supporters, officials, players, and coaches who explain what it means to be a community football club owned and democratically run by 2825 co-owners, each holding one voting share. FC United’s manifesto makes it clear this is football by the people, for the people. Football for the working class. “FC United seeks to change the way that football is owned and run, putting supporters at the heart of everything,” states the club’s website. “It aims to show, by example, how this can work in practice by creating a sustainable, successful, fan-owned, democratic football club that creates real and lasting benefits to its members and local communities.”

Around the time of the film’s release, construction began on FC United’s new 5,000-capacity stadium. After wandering for years playing home matches at rented grounds, most recently at Gigg Lane in Bury, members raised more than £2m through a share scheme, and secured additional funding from Sport England, the Football Foundation, the City of Manchester, and Manchester College. (Click here for a recent news story about the stadium.)

The extraordinary story of FC United putting people and poetry before profits is beautifully told in this brilliant documentary. Don’t miss it!